the gentle pitter-patter of rain was the last thing I heard when I closed my eyes, and the first when I woke up. I always tend to forget just how pleasant rain is, probably due to the fact that I hardly ever see a drop here. but when it does, it’s a nice reminder for me that, sometimes, change is good. but that doesn’t mean change is easy.

in the sphere of music specifically, change can take on different meanings. for me, change can be when a band you really like makes a complete left turn from anything they’ve done before (ie. what made them famous). some in the entertainment industry have a name for it: “career suicide”. others may call it self-sabotage. as for loyalists, possibly fans from the very beginning, no word may be more accurate to describe how they feel other than betrayal.

but sometimes that risk turns out to be the very catalyst that puts a band on the map, a gold record road to popularity and acclaim. or, it fails, and they are sentenced to relative obscurity.

such was the case for AFI (meaning, A Fire Inside), formed in 1991 while still in high school. AFI primarily flew under the mainstream radar, until nearly twelve years after forming: when everything changed with the release of their sixth album, Sing the Sorrow (2003).

AFI, and their start as a punk band.

over the last decade, AFI became a respected name in the Bay Area hardcore punk1 scene. aligning with punk rock’s do-it-yourself (DIY) and independent nature, AFI worked relentlessly to help foster the ethics they lived by. as part of the genre’s 90s revival (Green Day, Rancid, and The Offspring most famous to emerge from it), AFI’s explosive onstage energy, commitment to straight-edge2 and counterculture ethos resonated deeply with much of the raging punk youth, reeling from the socioeconomic turbulence of 1990s San Francisco.

in time, AFI was selling out shows—first small clubs, then theatres, and later frequent performers at one of punk’s revered meccas, 924 Gilman Street3. AFI, like punk itself, was staunchly opposed to anything corporate or mainstream, and hardcore attracted like-minded individuals and anyone who felt like an outsider in a world of insiders.

but change would soon come. by 1998, the four-piece had only two of its founding members left: lead singer Davey Havok and drummer Adam Carson (newcomers being guitarist Jade Puget and bassist Hunter Burgan). and with the lineup change, AFI had gradually sanded down the sharp edges of hardcore: for Davey, it meant the shredding of his vocal cords giving way to actual singing, his high register becoming more distinct, expressive, and melodic. what was once a wall-to-wall audial assault of sheer reckless abandon morphed into carefully curated and sequenced tracklists of enigmatic, thought-provoking, introspective, and even poetic songs. AFI was becoming a completely different machine altogether, and fans were already jumping ship.

in 2000, five albums in, the AFI found themselves at a crossroads: commit entirely to a new sound, or stay in their lane and stick to what they know? by this point, many major labels were vying to sign the band to a record deal. to wave the independent artist’s white flag to go mainstream would guarantee accusations of the band being the “s” word4, as had happened to acts like Nirvana and The Smashing Pumpkins—and ultimately traitors to the scene they helped to foster for nearly a decade.

in the words of Nick Lowe, circa 1976, “So it goes, so it goes, so it goes”.

mainstream success, and what set AFI apart.

AFI, to put it simply, was just something else, a clear-cut distinction from the skate- and pop-punk, ska and nu-metal bands that dominated Vans Warped Tour lineups years prior.

the year was 2002: AFI leaves the nest of independent punk label Nitro Records, and inks a major deal with DreamWorks Records.

this brought significant advantages for the follow-up album: financial freedom, with higher budgets for recording in nicer studios, and access to record producer legends like Butch Vig and Jerry Finn to give the album its anthemic, arena-ready, polished sheen. in this deal, the members made it clear that they wanted creative control of the band’s music and art direction, which DreamWorks readily supported. with the backing of a major label, and a complete change of sound on the horizon, it was evident—now more than ever—that AFI had shed the skin and identity of hardcore. some might say they broke the chains.

and, well, the rest is history: Sing the Sorrow came out in 2003, and catapulted the band into the mainstream with commercial and critical success. AFI, to put it simply, was just something else, a clear-cut distinction from the skate- and pop-punk, ska and nu-metal bands that dominated Vans Warped Tour5 lineups years prior. it was maximalist, dramatic, and more mature and grown-up than some of their contemporaries. the poetic introspection that once drove away waves of hardcore fans was now drawing in lifelong devotees, becoming fondly remembered soundtracks of adolescence and early adulthood.

the album cemented AFI’s place as a mainstream rock band, and became pivotal to the popularity of the aptly titled post-hardcore genre. it also stands today as a landmark in the emo and scene6 subcultures—the “Girl’s Not Grey” music video, played religiously on Fuse, would be the emo awakening for countless teens the world over.

in contrast to the devil-may-care attitude of 90s alternative rock, the album takes itself incredibly seriously, fully leaning into its cinematic, theatrical scope. this is immediately apparent from the opening track, welcoming the new AFI like ringing in the new year: a rousing chant set to reverberated tolling of bells, led by Davey’s skyscraper-like tenor (“Miseria Cantere”); soundscapes of a car driving through a rain-soaked street (“Silver and Cold”); a wildly technical, flashy guitar solo when solos were considered uncool (“Dancing Through Sunday”); a stripped-down singalong you’d wave a lighter to (“The Leaving Song”); and not one, but two not-so-hidden tracks to close out the album in gloriously weepy fashion: a spoken word interlude accompanied by piano and orchestra, followed by a ballad that disintegrates into distortions of noise and what once was (“This Time Imperfect”).

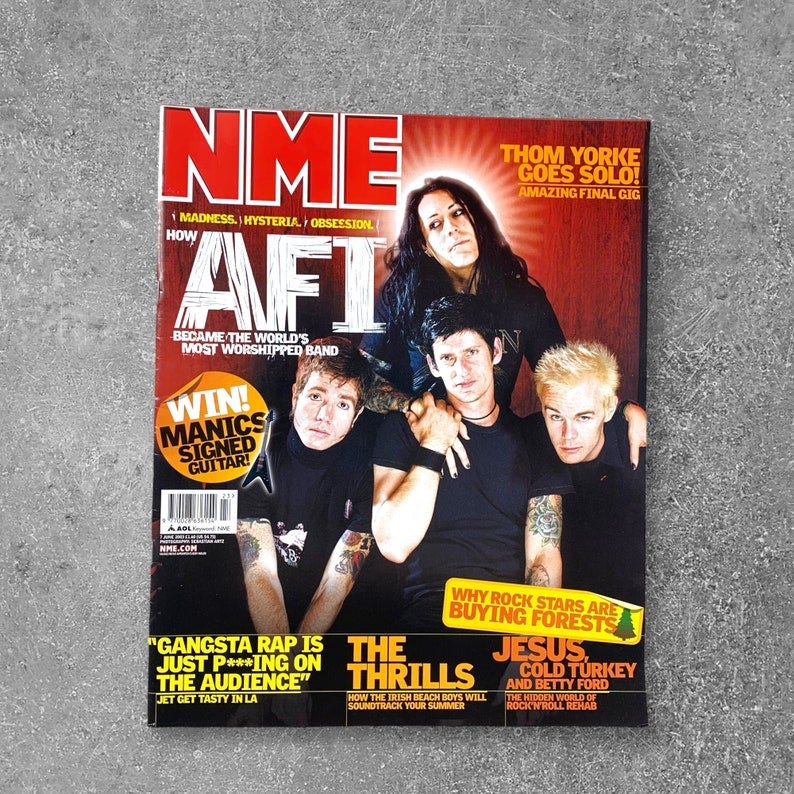

yes, AFI, twelve years removed from their inception, now finally had a worldwide platform to share their art. AFI became totalimmortal-ized in how it resonated with mainstream culture: “We dance in misery” scribbled in notebooks, the winged logo on the hottest of Hot Topic tees, and magazine cutouts of Davey and co. lining the inner walls of school lockers. the popularity was met with front cover appearances on widely known music magazines Alternative Press and NME.

AFI applied their DIY, hands-on approach to just about everything they did, including the band’s own image and marketing. they went from the old days of handing out flyers to their own shows, to the relatively unexplored, new interpretation of fan-to-artist interaction: the Internet, and its limitless potential to reach and connect with a worldwide audience. a cryptic worldwide scavenger hunt (led by surreal breadcrumb clues and videos) gave fans all the more reason to invest themselves in the music, gushing excitedly on internet forums and on afireinside.net. The Despair Faction, a fan club with paid membership, was an even greater incentive for the truly AFI devoted—you sent your payment (or begged your parents), and a mysterious, AFI-branded box would be sent to your doorstep: complete with a numbered membership card and exclusive goodies like posters, stickers, buttons, patches, and shirts (none of which would be found at a merch table). and most of all, the sacred grounds of the closely-guarded DF message board. it was just like hanging out backstage with the boys, along with other weirdos like you, all in your own little secret community.7 in a way, the DIY spirit of punk lived on in the band… just not sonically.

AFI helped set a precedent in the genre for having a strong visual identity; the distinct look and vibe (dare I say, era) became inseparable from the music. the visual storytelling and lyrics would also morph thematically from album-to-album: dark romantic (Sing the Sorrow), to 70s glittery glam (Decemberunderground, 2006), to New Romantic George Michael-meets-Morrissey hybrid (Crash Love, 2009), then to a princely, studded leather poster boy of doom and gloom (Burials, 2013)… all within the span of a decade. AFI’s penchant for goth-punk and glam rock theatrics was apparent especially in music videos and onstage getups: essentially, an affinity for a flair for the dramatic—aesthetic cues that would help establish a matte, full-coverage foundation for bands like Aiden, My Chemical Romance and Panic! at the Disco. Sorrow would even be nominated for a Grammy, for “Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package”.8

looking ahead.

but for the O.G. punks who sweated it out in small club shows, or screamed back “I Wanna Get a Mohawk (But Mom Won’t Let Me Get One)” at Davey at the Fireside Bowl in 1997, they quickly realized that AFI was never going back. as you can imagine, Sing the Sorrow was incredibly polarizing for fans in the 90s camp: some embraced the change and image; others were alienated—the “new” AFI was as un-punk as it could get: playing music and donning fashion styles considered as for “poseurs”. the typical AFI fan in 2003 also wasn’t decked out wearing Doc Martens and studded battle jackets9; they embraced the emo in all of its jet-black, straightened hair glory with skinny jeans and Vans.

some elements of AFI’s hardcore origins would be interwoven throughout the music, like the occasional fast tempos and gang vocals. but AFI would only stray further the more removed they became from 2003: the breakneck tempos and power chord changes that defined earlier songs were toned down to near non-existence, replaced with melodic passages, memorable riffs, and catchy singalong choruses. make no mistake, it was still the same band—the members were the same; but virtually everything about the quartet’s music and identity had completely changed… less Minor Threat, more The Sisters of Mercy and The Cure. gone was all trace of hardcore, and in came their unique blend of rock with heavy doses of electronic, new wave, 80s synth-pop, and a heavy dose of theatrics.

it could be easy for AFI to rehash future songs in the vein of Sing the Sorrow, to repackage and recreate its success. but the band has always looked forward, not backward. and when they do acknowledge their past (such as the 20th anniversary performance of Sing the Sorrow in full “for the first and last time ever” in 2023), it’s an honorable tribute to that evolution rather than trying to bury it out of shame or disowning its place in the band’s legacy. older songs are frequently woven into the live sets, much to the delight of those more in the punk camp, and it’s a joy to just see AFI still out there doing it (songs for the 12th album are rumored to drop this summer).

the solo and side projects of AFI’s members also speak of their musical versatility: Hunter, bassist, would embark on a funk/R&B take on 80s Prince (Hunter Revenge), Davey and Jade would pair up as an electronic duo (Blaqk Audio), and Davey, ever the chameleon, would channel his love for new wave and synth-pop by joining the supergroup DREAMCAR in 2016 (along with members of No Doubt, sans Gwen Stefani).

AFI, essentially, dove off of a figurative cliff, blindfolded, and desperately hoping someone—anyone—would be at the bottom to receive them. and if they fell flat on their face, it’s not like they’d be able to simply return to the hardcore scene, tail between their legs, and just say “my bad”. it just goes to show that the inconvenient reality for just about any pursuit is that risk does not always pay off. if anything, its purpose might be reduced to a parable of one’s reckless bravado, or a case of an upstart with incredible potential losing “the plot”. perhaps that’s what makes risks, risks.

more to come, in part two, and how change and risk relate to watches…

hardcore punk: a subgenre of punk rock that emerged in the late 1970s, notably within San Francisco, Washington D.C., Boston, and New York. by the 1980s hardcore evolved from punk with more aggression and faster tempos. while most wrote about social and political issues, some hardcore bands turned inwards, with lyrics of personal struggles, relationships, and emotions. core values of punk thrived on the backs of anti-establishment, non-conformist, do-it-yourself (DIY) ethics and code. oft-cited examples of hardcore are Black Flag, Bad Brains, and Minor Threat.

straight edge: a subculture of punk, originating in early 1980s Washington D.C.—a conscious departure from the nihilism and self-destructiveness that defined prior punk culture. those claiming to be straight edge typically abstain from alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, and occasionally promiscuity, though some may also adopt vegetarianism or veganism diets (in the case of AFI and other adherents).

924 Gilman Street: a.k.a. “Gilman”, a music club located in Berkeley, CA. since 1986, Gilman has been a non-profit, all-ages venue, and brought local East Bay and Northern CA punks together. Gilman was a stepping stone for the 90s punk revival. it is known to be a different take on punk culture—a safe haven from the recklessness that classified 1980s hardcore venues. a staunch supporter of independent music (and notorious for refusing to book major label acts), Gilman would famously ban Green Day from the club, following the release of their major label debut album, Dookie (1994).

“s” word: meaning sellouts… by the way, we keep things classy here ;)

Vans Warped Tour: commonly shortened to Warped Tour. first sponsored by skateboard shoe company Vans, it is a touring music festival held every summer with appearances in North America, Australia, and the UK. initially limited to mainly mostly skate-punk and ska acts, the festival would be known for pop-punk, post-hardcore, and metalcore bands in their lineups, such as blink-182 and Paramore, The Used and Taking Back Sunday, Saosin and Underoath, etc.

emo and scene subcultures: what’s really considered “real” emo has been argued in discussion boards for decades—basically, emo emerged in the mid-1980s as a variation of hardcore centered around emotional, confessional lyrics, much unlike typical punk. emo went mainstream in the 2000s, except way more accessible and marketable as a music and fashion trend. for the purpose of this and the next article, it’s specifically the subculture devoted to bands like The Used, Jimmy Eat World, Dashboard Confessional, Fall Out Boy, and others named in this article… especially AFI.

a candid look at the history of Despair Faction can be found here in this Vice article: “An Oral History of Despair Faction, AFI’s Tight-Knit Fan Forum”. if you want to know just how big of a thing being an AFI fan was at this time, you should give it a read.

nominated for a Grammy: yes, really, and in 2004. credit to Morning Breath, Inc., who did the packaging for Sing the Sorrow, and would be approached again for the album’s 20th anniversary box set. it is the absolute coolest limited edition I’ve ever seen for music—if you love art and cool little trinkets, you must absolutely see the video by @morningbreathinc on Instagram.

battle jackets: a visual, identifying mark of a punk’s favorite bands and ethos. typically a black or navy denim jacket (or vest, by cutting off the sleeves) and frequently adorned with studs, patches of band logos, and lyrics or slogans the wearer strongly identified with. the term “battle jacket” became popular lingo in the 1980s metal scene, and has been adopted since by some punks.